By Daniel Kraker

http://stream.publicbroadcasting.net/production/mp3/knau/local-knau-956707.mp3

Flagstaff, AZ – A couple dozen protestors marched outside the public hearing in Flagstaff. Their message was loud and clear.

"No uranium mining, protect the Grand Canyon," they chanted.

Inside, the actual meeting was more subdued. Dozens of federal officials were on hand to discuss the one thousand page environmental impact statement that outlines four potential courses of action. They range from doing nothing, to setting aside one million acres on both the North and South Rims from any new mining claims for the next 20 years.

"Certainly in the public there is a lot of controversy," says Chris Horyza. He's overseeing the project for the Bureau of Land Management.

"There are communities in some areas that see it as an economic engine. There are communities in other areas that see it as a potential barrier to economics, especially south of the Grand Canyon where tourism is such an economic engine."

Then, there are people who see uranium as an important clean energy source. And others who worry about potential environmental impacts on wildlife and groundwater. Matthew Pitsoui is one of them. He's a member of the Havasupai Tribal Council who lives deep inside a side-gorge of the Grand Canyon.

"The most important thing is that we protect the water," he says. "We are people of the blue-green water, that's where we get our name from, the sacred water, sacred springs that flow from the Canyon, and to contaminate that will contaminate us as a people."

Potential groundwater contamination is one of the most contentious issues surrounding uranium mining near the Grand Canyon. Some scientists believe mines could provide pathways for contaminated water to eventually leech into the Colorado River.

The U.S. Geological Survey studied the area's groundwater for the environmental analysis.

John Hoffman, who directs the USGS Arizona Water Science Center in Tucson, says that when drilling occurs, "Uranium is more mobilized. And we do know that concentrations of uranium does increase in certain areas around the mine. Particularly at the bottom of their shaft. So there could be localized contamination of the water."

Hoffman's team collected around one thousand water samples. About 15 of them had uranium concentrations greater than the EPA standard for drinking water. But Hoffman says it's hard to say why.

"So it was difficult for us to discern as to whether or not the high uranium concentrations were naturally occurring," he says, "or anthropogenic, by that I mean induced by human activities."

That uncertainty is all the more reason to not allow new mining, says Roger Clark. He's with the Flagstaff-based Grand Canyon Trust.

"There's not enough data to say conclusively what the exact impacts are going to be on the water, wildlife, a lot of things," he admits. "But where we do have data, there is information that says there will be impacts, and so why go there, we don't need this, this is not in the national interest."

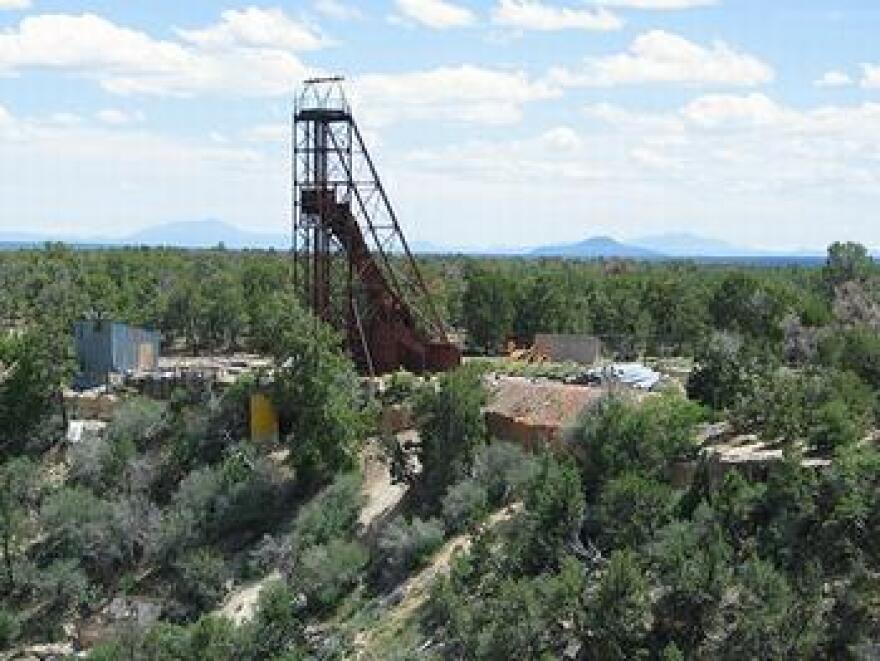

A few years ago the price of uranium spiked from $10 to about $130 per pound. That caused mining companies and some individuals to stake more than ten thousand claims near the Grand Canyon, which has some of the highest grade uranium ore in the country.

The BLM estimates that only a dozen, to maybe 30 of those claims will actually become producing mines. Gregory Yount believes he has one of them.

"I'm fairly confident that I have a very, very good chance of having ore grade mineralization, one of the claims has uranium at the surface, which is very rare," he explains.

Yount isn't a big mining company executive. He's an engineer and self-described treasure hunter from Chino Valley. A couple years ago he formed an LLC and made three claims south of the Canyon. He was all set to test drill for uranium two years ago.

But then Interior Secretary Ken Salazar blocked any new development until the department could further study the issue. Now he worries he could be prevented from mining for at least two decades.

"The work I've done on those two targets," he says, "it probably amounts to 30, 40 thousand dollars, and I'm an individual, I'm an American citizen, this is something that I've been working on for essentially three and a half years, so I'm obviously very concerned that the investment I made is basically going to be taken."

Yount believes there are a lot of problems with the government's environmental analysis. He says he's already written 25 pages of comments. The public has until April 4th to weigh in on the proposals.