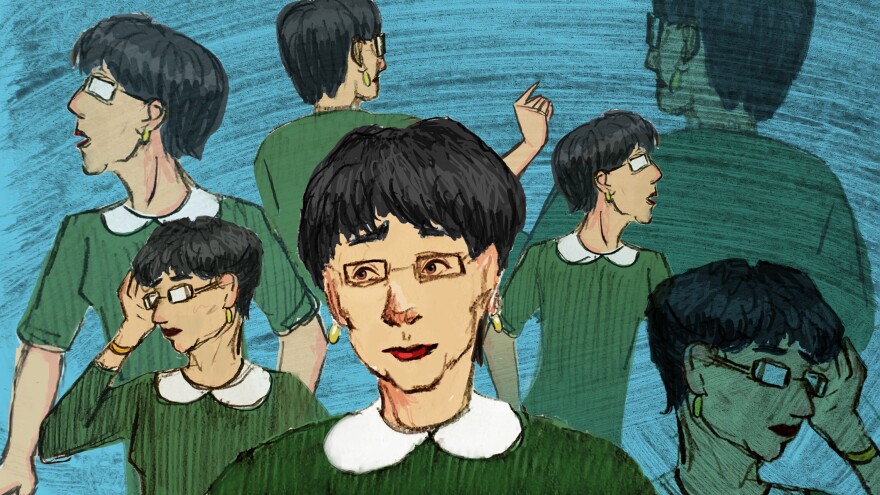

When Cathy Fields was in her late 50s, she noticed she was having trouble following conversations with friends.

"I could sense something was wrong with me," she says. "I couldn't focus. I could not follow."

Fields was worried she had suffered a stroke or was showing signs of early dementia. Instead she found out she had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD.

Fields is now 66 years old and lives in Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla. She's a former secretary and mother of two grown children. Fields was diagnosed with ADHD about eight years ago. Her doctor ruled out any physical problems and suggested she see a psychiatrist. She went to Dr. David Goodman at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, who by chance specializes in ADHD.

Goodman asked Fields a number of questions about focus, attention and completing tasks. He asked her about her childhood and how she did in school. Since ADHD begins in childhood, it's important for mental health professionals to understand these childhood experiences in order to make an accurate diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood. Online screening tests are available, too, so you can try it yourself.

Goodman decided that Fields most definitely had ADHD.

She's not alone. Goodman says he's seeing more and more adults over the age of 50 newly diagnosed with ADHD. The disorder occurs as the brain is developing, and symptoms generally appear around age 7. But symptoms can last a lifetime. For adults, the problem is not disruptive behavior or keeping up in school. It's an inability to focus, which can mean inconsistency, being late to meetings or just having problems managing day-to-day tasks. Adults with ADHD are more likely than others to lose a job or file for bankruptcy, Goodman says. They may overpay bills, or underpay them. They may pay bills late, or not at all.

For Cathy Fields, the more she thought about it, the more she realized distraction and the inability to focus was the story of her life. It was also the story of her mother's life. Her mother "never got things done," Fields says.

This is typical, according to Goodman; ADHD often runs in families. According to Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, or CHADD, an advocacy group, the disorder can be inherited. If a parent has ADHD, the child has more than a 50 percent chance of also having it. If a twin has ADHD, the other twin has up to an 80 percent chance of having the disorder.

But because many of today's older adults grew up during the 1950s and '60s when there wasn't much awareness of ADHD, many were never diagnosed. And increasingly, Goodman says, he's seeing more and more patients who are concerned about dementia but who actually have ADHD — just like Cathy Fields.

Goodman also sees patients who are diagnosed after their child or grandchild gets a diagnosis. "That's the genetic link," says Goodman, "from Grandmom to Mom to daughter."

About 60 percent of children with ADHD go on to become adults with ADHD, says Dr. Lenard Adler, a professor of psychiatry at the New York University School of Medicine. As these older adults weren't diagnosed, they learned to work around the problem, Adler says. They developed coping systems to deal with their inability to focus or pay attention.

That was the case with 65-year-old Kathleen Brown, a retired nurse who lives in Maryland. She was never diagnosed as a child, but she "knew something was wrong," she says.

Brown didn't learn to read until she was 12. And, she says, she had to work a lot harder in school than other kids did for the same grades. When she went to nursing school, Brown made sure she sat in the first row during lectures so she wouldn't miss anything or be distracted. And when it came to testing, she says, she literally set her desk up in the back of the class, facing a corner.

When she finally got diagnosed and prescribed medication, Brown says, the change was "stupendous." She's not scattered, and can start projects and finish them. "I wish I had it when I went to school 25 years ago," Brown says. "It would have helped me for sure."

Like children with the disorder, adults with ADHD are treated with medication, psychotherapy, or a combination of treatments. ADHD medication works just as well for adults as it does for children, but there is a word of caution. Older adults often have other health problems, like high blood pressure and heart disease. So doctors need to be careful when prescribing ADHD medications, which are typically stimulants like Adderall or Ritalin.

For older patients, an ADHD diagnosis can be a huge relief. If you've spent your whole life with a disorder for which people said you were lazy, stupid, incompetent, says Goodman, "It's liberating to realize the impairments are the result of a treatable disorder and not a character weakness or intellectual inadequacy."

So for older people with memory and focus problems, Goodman says, it's important for doctors to check for ADHD. While it could be cognitive decline, there's growing awareness that it could also simply be the symptoms of a lifelong childhood disorder.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.